(Reuters): President Yoon Suk Yeol of South Korea made the surprising announcement on Wednesday that he was canceling the martial law that he had imposed just hours earlier. Following a contentious discussion, the South Korean parliament firmly rejected his plan to restrict media freedom and political participation.

Citing the necessity to combat "anti-state forces" inside the internal political opposition, Yoon declared martial law late Tuesday night. One of the most severe political crises in South Korea's recent history was brought on by his acts, which immediately incited outrage among both lawmakers and citizens.

In response to the martial law announcement, South Korea's parliament unanimously rejected it. The government immediately reversed course, with sources indicating that the cabinet agreed early Wednesday to lift the martial emergency order. Protesters outside the National Assembly cheered and chanted "We won!" in response to this news.

The largest opposition party, the Democratic Party (DP), promptly demanded President Yoon's resignation or impeachment. Senior DP MP Park Chan-dae stated that even if martial law were lifted, Yoon should face treason charges. He said that the president's conduct demonstrated that he was no longer fit to lead and that Yoon should resign.

The political turbulence generated replies from a variety of experts, including Danny Russel, a vice president at the Asia Society Policy Institute. He noted that South Korea had narrowly escaped a grave situation, but cautioned Yoon that adopting such an extreme measure could jeopardize his own political destiny.

Following the relaxation of martial law, the South Korean won began to rebound, rising from a more than two-year low against the dollar. Additionally, exchange-traded funds linked to South Korean stocks lessened their losses following Yoon's reversal of the directive.

The National Assembly immediately rejected Yoon's declaration of martial law, which he defended as a tactic against his political rivals, with 190 lawmakers voting against it. He was pressured to change his mind by his own party, the People Power Party, highlighting internal resistance. According to South Korean legislation, if a majority of lawmakers call for the immediate revocation of martial law, the president must do so.

The political crisis in South Korea, a crucial US ally and significant Asian economy, shocked the world community. The country has been a democracy since the 1980s, but the proclamation of martial law aroused concerns about the stability of its democratic institutions.

Following the martial law announcement, South Korea's military said that legislative activities and political party operations would be prohibited, and media outlets would be subject to martial rule control. There were also reports of helmeted military trying to enter the parliament building, resulting in a violent standoff. The soldiers were pushed back by parliamentary aides using fire extinguishers.

The White House responded to Yoon's decision by expressing relief that martial law had been removed. Yoon was praised by a U.S. administration official for upholding the National Assembly's decision to withdraw the directive, emphasizing the significance of preserving South Korea's democratic processes.

Kurt Campbell, U.S. Deputy Secretary of State, had earlier expressed grave concern about the events and emphasized that the United States was keeping a close eye on the situation. With 28,500 troops positioned there to protect against North Korea's threat, South Korea has a sizable US military presence.

Yoon did not cite a direct danger from North Korea as the cause for declaring martial law. Instead, he emphasized what he thought were actions by domestic political opponents that jeopardized national security. His statement was the first time martial law was enforced in South Korea since 1980.

Former top US diplomat for East Asia Danny Russel issued a warning, saying that North Korea would gain from South Korea's political unrest. He claimed that domestic turmoil and political ambiguity would benefit North Korea, which may take advantage of a divided South Korea.

Former prosecutor Yoon won the presidency in 2022 after a fierce electoral battle. Significant contributors to his triumph were scandals, gender concerns, and widespread dissatisfaction with the government's economic policies. However, he has had a low approval rating, remaining at roughly 20% for several months.

In this year's April parliamentary elections, opposition parties defeated Yoon's party easily, securing more than two-thirds of the seats in the National Assembly. This failure made it much more difficult for him to pass legislation and exposed him to attacks from political opponents.

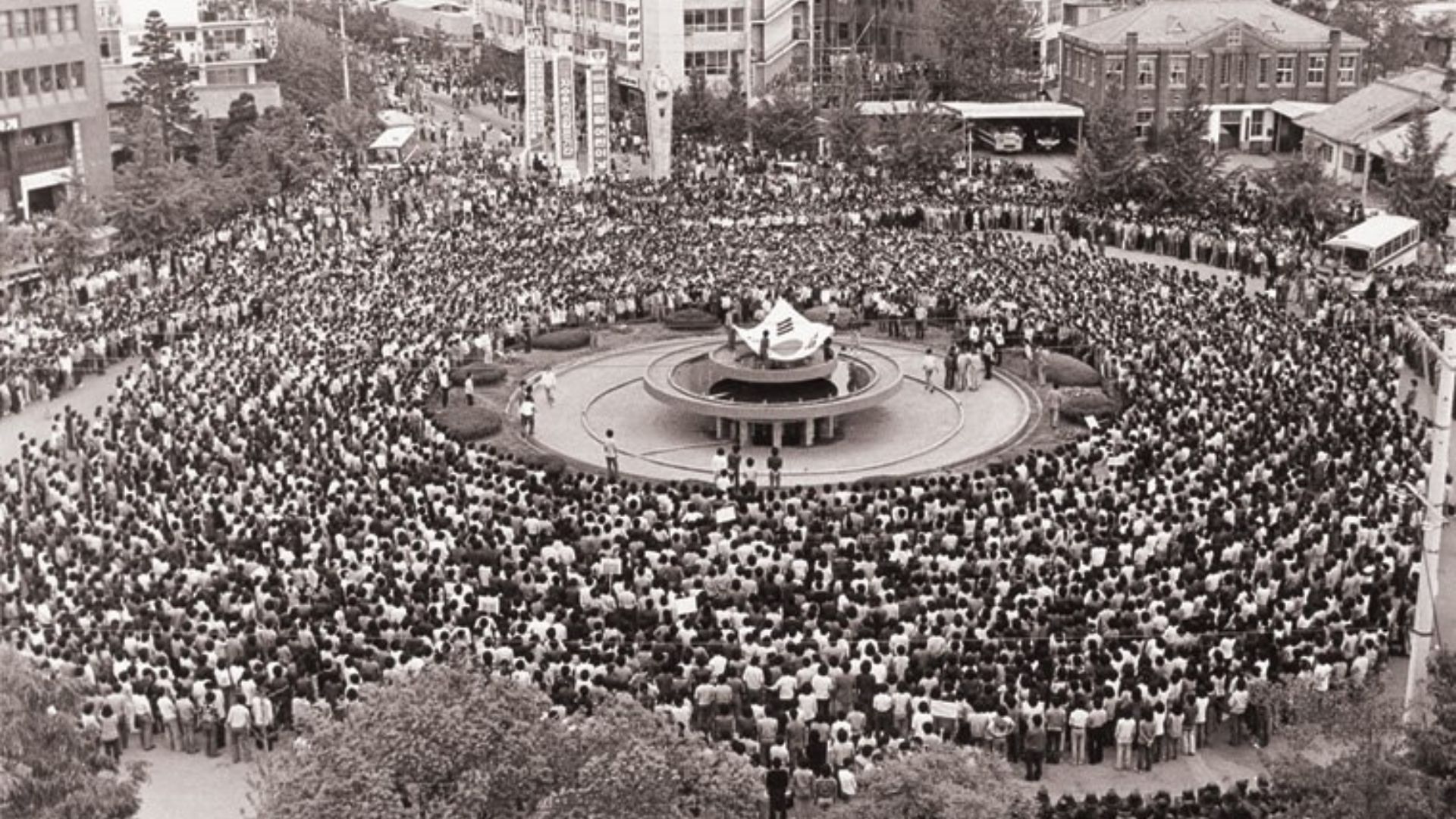

There have been more than a dozen declarations of martial law since South Korea became a republic in 1948. The most notorious occurred in 1980 when a group of military commanders under the leadership of Chun Doo-hwan compelled then-President Choi Kyu-hah to declare martial law in order to quell student demonstrations demanding the return of democratic governance and opposition activities.

In 1980, a very contentious period in South Korea's history, martial law resulted in severe political persecution. Many South Koreans were concerned about the possible return of authoritarian methods when Yoon's most recent declaration of martial law was compared to this troubled time.

Removing the declaration of martial law, however, does not fully resolve the political issue. Several of Yoon's detractors, including Democrats, are still calling for responsibility for what they see to be an abuse of presidential authority. There is growing pressure on Yoon to come to court and take responsibility for his acts.

Yoon's leadership and political savvy are also called into question by his abrupt declaration of martial law. In addition to worsening domestic political differences, the action jeopardized South Korea's standing as a stable democracy abroad.

The National Assembly was crucial in opposing the president's order, and the lifting of martial law was a major win for South Korea's democratic institutions. But since Yoon's political future is still up in the air and his authority is still being challenged, the crisis' political effects are probably going to last.

Deep rifts in South Korean politics and society have been revealed by the crisis, and the nation may now face more instability. The situation is still uncertain, and it's not certain if Yoon's government will be able to repair the harm to its reputation.

The issue of martial law is making South Koreans wonder about the future of their democracy and the role of the military in politics. Discussions concerning South Korea's legislative, executive, and military branches of government have been triggered by the occurrence.

South Koreans are left to wonder about the future of their democracy and the military's role in politics after the martial law crisis. Discussions concerning the division of authority between the legislative, executive, and military departments of South Korea have been triggered by the occurrence.

Despite its quick resolution, the aftermath raises serious questions about how strong South Korea's democratic institutions are. Given its strategic importance in the region and its relationship with the United States, the international community will continue to closely monitor South Korea's development.